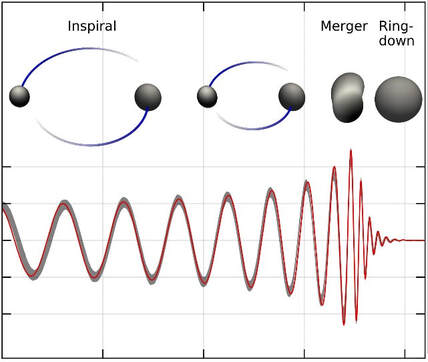

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHT: MASSIVE OVERCONTACT BINARY STARS OPEN A NEW WINDOW TO STELLAR EVOLUTION8/12/2020  The massive O4.5 V + O5.5 V binary VFTS 352 in the Tarantula Nebula (location indicated by the red cross) is one of the shortest-period and most massive overcontact binaries known. Recent theoretical studies indicate that some of these systems could ultimately lead to the formation of gravitational waves via black hole binary mergers through the chemically homogeneous evolution pathway. Image credit: ESO / M.-R. Cioni / VISTA Magellanic Cloud survey / Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit. In 2015, the first direct observation of gravitational waves was made by the Advanced Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (aLIGO) (Abbott et al. 2016). The detected signal, known as GW150914, not only provided the most rigorous test of General Relativity—Einstein’s theory of gravity—it was also the first observation of two black holes merging. This confirmed the existence of black holes, binary stellar-mass black hole systems, and proved that they can merge within the current age of the Universe. Since that first detection, aLIGO has detected many more black hole mergers but scientists are still puzzled: many of the black hole mergers that aLIGO has detected so far, including GW150914, involve systems with the component black holes weighing-in at more than 20 solar masses each—some much more. These are massive black holes—heavier than any previously known black holes from X-ray binary observations—which raises the question: how did they form? Our recent study seeks to answer that question. aLIGO records (part of) the inspiral, merger, and ring-down of the orbiting black holes—as shown in figure 1[JR1] . aLIGO can only record these events if they occur within its operating lifetime—that means that the progenitor stars must collapse to black holes before they merge, and the subsequent orbiting black holes must spiral in towards each other and merge within the age of the Universe. For that to happen, the black holes must be big and close together; however, progenitor stars big enough and close enough to produce a binary black hole (BBH) system that would spiral in and eventually merge within the age of the universe, and that could generate gravitational waves detectable by aLIGO, would be too big and too close; so these progenitor stars merge first and then collapse into black holes. Thus, the aLIGO detections raise the intriguing questions: how did the black holes get so massive? and how did they get so close together? Chemically Homogeneous Evolution (CHE) has been proposed as a possible solution. Rapid spinning stirs a star leading to its interior becoming homogeneous, and possibly fusing entirely rather than just the core. A hot, rapidly spinning, chemically homogeneous star doesn’t expand as it ages in the way a conventionally evolving star does. The chemically homogeneous model begins with a pair of close, massive stars rotating around each other extremely rapidly—so close that they become tidally locked, causing the stars to spin rapidly on their own axes. The component stars of this massive, overcontact binary eventually collapse into massive black holes, which are now close enough to spiral in and merge within the age of the Universe. For the first time, we simultaneously explore conventional isolated binary star evolution and chemically homogeneous evolution under the same set of assumptions. This approach allows us to constrain population properties and make simultaneous predictions about the gravitational-wave detection rates of BBH mergers for the CHE and conventional formation channels. This joint model for the classical and CHE isolated binary evolution channels will enable simultaneous inference on binary evolution model parameters and the metallicity-specific star formation history once the full trove of observations from the aLIGO third gravitational-wave observing run is available. Ultimately, the relatively short delay times of CHE BBHs make them ideal probes of high-redshift star formation history; their high masses make them perfect targets for third-generation gravitational-wave detectors with good low-frequency sensitivity, such as the Einstein Telescope or the Cosmic Explorer. Written by OzGrav PhD student Jeff Riley - Monash University Link: https://arxiv.org/abs/2010.00002

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

|

- Home

- About

-

Our People

- Chief Investigators

- Partner Investigators

- Associate Investigators

- Postdocs and Students >

- Professional & Outreach staff

- Governance Advisory Committee

- Scientific Advisory Committee

- Executive Committee

- Equity & Diversity Committee

- Early Career Researcher Committee

- Professional Development Committee

- Research Translation Committee

- OzGrav Alumni

- Research Themes

- Education and Outreach

- Events

- News/Media

- Contact Us

- Home

- About

-

Our People

- Chief Investigators

- Partner Investigators

- Associate Investigators

- Postdocs and Students >

- Professional & Outreach staff

- Governance Advisory Committee

- Scientific Advisory Committee

- Executive Committee

- Equity & Diversity Committee

- Early Career Researcher Committee

- Professional Development Committee

- Research Translation Committee

- OzGrav Alumni

- Research Themes

- Education and Outreach

- Events

- News/Media

- Contact Us

RSS Feed

RSS Feed