Artistic impression of the Double Pulsar system, where two active pulsars orbit each other in just 147 min. The orbital motion of these extremely dense neutrons star causes a number of relativistic effects, including the creation of ripples in spacetime known as gravitational waves. The gravitational waves carry away energy from the systems which shrinks by about 7mm per days as a result. The corresponding measurement agrees with the prediction of general relativity within 0.013%. Credit: Michael Kramer / MPIfR

2025 Frontiers of Science Award for the international Double Pulsar research team The research paper “Strong-Field Gravity Tests with the Double Pulsar” led by OzGrav Partner Investigator Michael Kramer (Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, MPIfR) and including OzGrav Chief Investigator Adam Deller (Swinburne University) along with an international research team was published in the […]

2025 Frontiers of Science Award for the international Double Pulsar research team

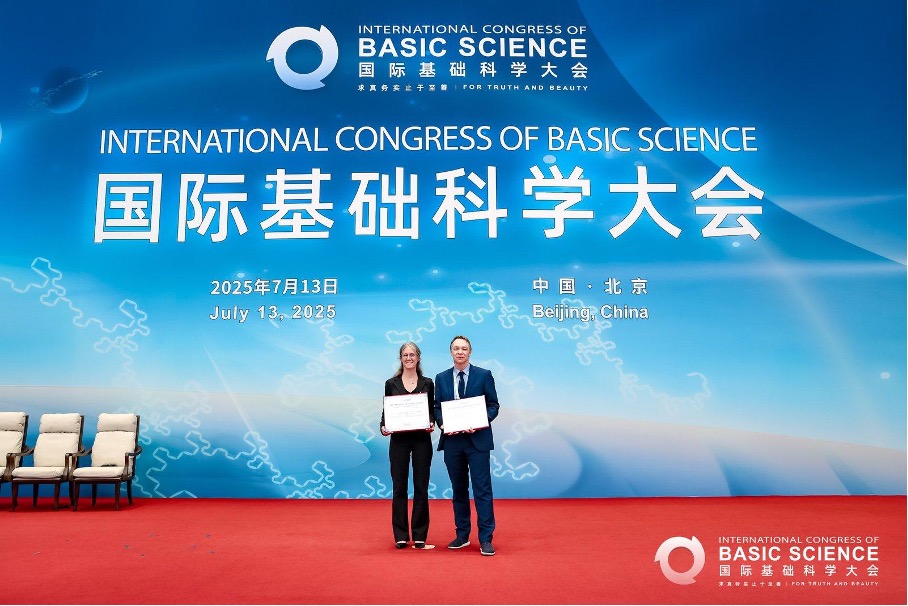

The research paper “Strong-Field Gravity Tests with the Double Pulsar” led by OzGrav Partner Investigator Michael Kramer (Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, MPIfR) and including OzGrav Chief Investigator Adam Deller (Swinburne University) along with an international research team was published in the journal “Physical Review X” (Kramer et al. 041050, December 13, 2021). Their work received the Frontiers of Science award within the category “Astrophysics and Cosmology – theory” from the International Congress for Basic Science (ICBS). The award ceremony took place at the China National Conference Center (CNCC) – on July 13, 2025.

More than 100 years after Albert Einstein presented his theory of gravity, scientists around the world continue to search for tiny deviations from its predictions that would point the way to a new theoretical understanding of the laws that govern the Universe. Binary radio pulsars – rapidly spinning neutron stars whose beamed radio emission can be observed as precise clock ticks from the Earth – are ideal laboratories for searching for such deviations. The “double pulsar” system, which was the subject of the paper honoured by the ICBS, is the best such system currently known for making these ultra precise tests. “We studied a system of very compact stars to test gravity theories in the presence of very strong gravitational fields,”, states the research team’s leader, Michael Kramer from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR) in Bonn, Germany. “To our delight we were able to test a cornerstone of Einstein’s theory, the energy carried by gravitational waves, with a precision that is 25 times better than with the Nobel-Prize winning Hulse-Taylor pulsar.”

Apart from the loss of orbital energy through gravitational waves, other relativistic effects such as the periastron advance of the system (which has precessed around a full turn since its discovery over 20 years ago!), relativistic time dilation, and spacetime curvature have all been precisely measured in the double pulsar system, with every result agreeing with Einstein’s predictions to within the measurement uncertainty.

Such tests are only possible through careful calibration of the observed pulsar “clock ticks” for other effects that are unrelated to general relativity. As one example, the motion of the pulsar relative to the Earth, and its acceleration in the gravitational field of the Milky Way, contribute to the observed change in its orbital period. Fortunately, these effects can be calculated and corrected if the distance to the double pulsar and its motion on the sky are known. Prof Adam Deller led additional observations that measured tiny shifts in the position of the double pulsar system on the sky to provide these corrections. “By measuring how the double pulsar’s position shifted over the course of a year as the Earth orbits the Sun, we can infer how distant it is” said Prof. Deller. “But the position shifts are tiny – like seeing an ant crawl around a button from 5,000 km away!”

This combination of diverse effects produced by a system of two strongly self-gravitating bodies with extreme spacetime curvature makes the Double Pulsar a unique testbed — not only for general relativity but also for various competing theories, some of which have been significantly constrained or even excluded by this experiment.

“We are very pleased with the award honouring our work with the Double Pulsar which is the result of a collaboration with great colleagues, who together allowed us to combine our precision experiments with a rigorous theoretical understanding,” concludes Michael Kramer.

Original Paper

Kramer et al. Strong-Field Gravity Tests with the Double Pulsar, 2021, Physical Review X, December 13, 2021 (DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.11.041050).

https://journals.aps.org/prx/accepted/a7077K4fR4216c02853742f061ca5a31085788a3e

Further Information/Links:

Fundamental Physics in Radio Astronomy. Research Department at MPIfR

https://www.mpifr-bonn.mpg.de/research/fundamental

The 2025 Frontiers of Science Award

https://www.icbs.cn/site/pages/index/index?pageId=1fe7d1cf-c69c-47bd-a2fa-3d5731ca2610